I’ve been in reflective mood recently. My only daughter left home for university last month. My role as a mum has changed, my nest is empty. As I – and doubtless countless others before me – have found, at pivotal times in my parental role I remember my own parents as the realisation of what they went through with me sinks in.

I’ve been in reflective mood recently. My only daughter left home for university last month. My role as a mum has changed, my nest is empty. As I – and doubtless countless others before me – have found, at pivotal times in my parental role I remember my own parents as the realisation of what they went through with me sinks in.

How tolerant, calm and wise they were, how well they hid their feelings when I left home. For 18 years my daughter has been a huge part of my everyday life. I’m the youngest of three siblings, the oldest of whom is a decade older than me, so when I flew the coop it brought to an end for my parents not 18, but 28 years of raising children. I’m only now appreciating just how difficult that time must have been for them, particularly mum, who invested so much emotion into raising us three. My mum and dad will have known, perhaps even more than I do now, the curious combination of sadness and joy that I’m experiencing as my daughter settles into her adult life away from home.

To make this period even more poignant, Invisible Ink, a novel that I wrote when both my parents were dying is to be published next month. One of its characters is influenced by my mum’s last years as she developed dementia and we, her family, placed her in a nursing home. Invisible Ink is fiction – its chief protagonist is a 36-year-old male lawyer, Max. So hardly me. But the guilt that pervades it is very much mine.

Rereading it before signing off the final proofs I was reminded how little I knew about dementia when mum was alive. How ignorant, confused and frustrated by mum’s condition I was back then – characteristics shared by Max, albeit in heightened, fictional form.

It was only by complete chance that I connected with my mum the day before she died. It was Christmas Eve, and knowing her love of the Nine Lessons and Carols, I chose to listen to the service from King’s College, Cambridge on the radio, with her. The familiar notes of the solo chorister’s voice opening Once in Royal David’s City touched mum’s soul and, ill and close to death as she was, she opened her eyes. It was a deeply moving moment that remains with me still, and which I wrote about here.

Now though, through my blogs, and several years after I completed Invisible Ink (publishing can be a long old business), I understand so much more about the condition. I know the power of familiar music and songs, of the rhythms and inflections of much-loved poems when spoken aloud, of long-held, deeply buried skills – whether they be sinking golf putts, arranging flowers, whittling wood or planting bulbs – to reach out to, comfort and touch the hearts of those with dementia, even when the condition is advanced. I wish I’d been aware of all this earlier.

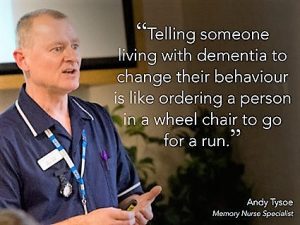

Unlike me, some people possess natural skills in this field and/or are trained in how to connect with others who have lost the common powers of communication. Andy Tysoe, a specialist dementia nurse based in Chester, is just such a person; his tireless mission to improve the lives of those with the condition goes far beyond the call of duty.

A Dementia Champion, Andy has created 5,500 dementia friends and delivered 200 of his tailor-made DementiaDO training sessions which incorporate both NHS and Alzheimer’s Society features. Recently, in the run-up to @FabChangeDay on 17 October he’s been tweeting daily #dementiaDO post-its written by some of those who have attended his courses. Simple, true, they hit home: “Ppl with dementia have invisible disabilities. They need time, understanding, US!”, “”Don’t forget that people with dementia cannot help it, they didn’t ask for this 2 happen to them”

A Dementia Champion, Andy has created 5,500 dementia friends and delivered 200 of his tailor-made DementiaDO training sessions which incorporate both NHS and Alzheimer’s Society features. Recently, in the run-up to @FabChangeDay on 17 October he’s been tweeting daily #dementiaDO post-its written by some of those who have attended his courses. Simple, true, they hit home: “Ppl with dementia have invisible disabilities. They need time, understanding, US!”, “”Don’t forget that people with dementia cannot help it, they didn’t ask for this 2 happen to them”

The latest to benefit from Andy’s enthusiasm are a group in the north-west of England affected by Posterior Cortical Atrophy (PCA), a rare form of the condition which initially affects vision and spatial awareness more than memory. Among them is 57-year-old Paul Bulmer, a former IT consultant diagnosed with PCA four years ago, and his wife (and now carer) Alison, from Helsby.

They feature in a recently released NHS England film which opens with an evocative and nostalgic blast from the past as a steam train pulls out of Bury Bolton Street station in Greater Manchester. On it, along with other members of the north-west PCA support group, are Paul and Alison, a former teacher.

For, as Andy discovered when the two of them were talking, Paul’s father was an engine driver with a lifelong passion for trains. Others might have noted this with interest and then simply got on with their lives. Not Andy. He immediately understood the significance of what he’d just heard and determined that Paul should, if at all possible, get to ride on the foot plate of a steam train.

Paul & Alison Bulmer at an Alzheimer’s Research UK half marathon about 18mths ago (Sadly, Paul can no longer run)

Alison told me just how much railways mean to her husband. “Paul remembers standing with his dad as the last train left Gisborough train station at the time of the Beeching cuts. He recalls having his photo taken with his dad. It is deep in his memory – the sights, the sounds, the smells”.

Keen to tap into Paul’s long-held memories, Andy planned a train trip for the PCA group from Bury Bolton to Rawtenstall and back. Alison knew that her husband would enjoy the day because he could relax in the company of a group who understand his condition and who don’t hurry him or have any expectations, but she had no idea that Andy had a surprise in store for Paul.

“When Andy asked him if he’d like to go on the foot plate it was an emotional moment and a few tears were shed”, she said. “But they were poignant tears”.

I bet they were. Once achieved, Andy’s mission seems such an obvious one, but how many of us – even if trained in dementia care – would a) realise its importance to someone like Paul Bulmer and b) put in the effort to make it happen?

It is these moments, these seemingly small but emotionally big moments, that I am privileged to write about nowadays. The experience of doing so, the people I’ve met since I set up my blog, have changed my view of the world. I think they’ve made me kinder and less impatient; they teach me by example and they make me stop and think.

Whatever life throws at my daughter in the coming years, I hope that having seen her granny with dementia and having read some of what I’ve written about the condition, she’ll have a greater understanding of what it is and how life can be made so much better for those who have it in countless simple yet meaningful ways. Somehow, knowing Emily, I think she will.

***

You can buy Christmas cards painted by Paul Bulmer in aid of Rare Dementia Support (an organisation which provides specialist support for people affected by rare dementias) here: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/6XJRG7N

A poignant and beautifully written piece.

I am struggling so much in dealing with the absence of my boys. Nothing in my life is the same. I miss them so much.

Thanks Jaq. I know; it’s such a strange combination of feelings – Emily is very happy so I’m very happy. But I do miss her. xx

Really thoughtful blog Pippa and it was only the other day I was talking about my mum’s last months and days and I was saying I wish I’d known what I know now about the NHS as her last days were not good.

The anniversary of her birthday is at the end of this month so I am always reflective in October as the seasons change.

I’m sure your daughter will have learned a lot from you and have taken that wisdom with her to University. Before I went to college, just a year after my mum’s first diagnosis of cancer, she sat me down to say that if she died I was not to come home and look after my brother and dad which she knew would have been my first instinct.

I’m sure she was sad to see me go whilst also being pleased for me to realise my ambition to become a teacher and looking back that was even more brave as at that time we didn’t know if she’d survive.

So pleased to hear your daughter is happy being away and that whilst missing her take comfort you’ve helped her get there.

Such a lovely blog Pippa ! Brings back memories of M and H flying the nest and I even had similar feelings when R and E also started at Uni. But to know they are happy and secure in their new life makes it all worth while .? X

It does indeed. Thanks Pat. x

Christine, thank you so much for leaving such a thoughtful message. Strange, transitional times for me, but yes, I’m taking huge comfort in knowing that Emily is happy. And it is only right and natural that she flies the nest. But still ….

Another superb piece Pippa, beautifully eloquent. Enjoyed reading immensely – I still recall Emily’s first birthday when I decided to trade Bermuda for Clapham; my early onset maternal self, aged 11 (then) – though little changes! The maternal side, I put a large amount of that down to Grandma: such an amazing comforting woman, so generous of spirit. SO sorely missed. Looking forward to your next blog and more importantly, reading a copy of Invisible Ink!!! Thrilled Em is having a ball – sending lots of love to you all, x